Quite a while before my father died (nearly thirteen years ago) he started writing down some of his memories. It has long been my intention to collate all the material, I think maybe this trip has been the impetus to make a start on putting together some of my parents' memories. So, when I got back to Lancaster I went up into the loft to retrieve all his writings and mish mash of photos. I realise the project is going to be a long one!

My father's grandfather, Thomas, retired to Fryup when he was 65. This is what my father remembered of Thomas' funeral, (he would have been 12 when Thomas died).

Grandfather’s funeral in the thirties John Featherstone

There was always something a bit awesome about the parlour; nobody went into it except on Sundays, and not very often then. I knew the prickly feel of the horsehair upholstered chairs, and marvelled at the black tablecloth which had my grandparents’ names embroidered in a circle at the centre, and there was a work basket which contained, among other things, a birthday book bound in blue and gold, with gilt edges. But on that day the coffin dominated the room, on a large, brass-knobbed bed. My cousins and I had been brought in to view the lying-in-state of our grandfather. The damask serviette was lifted from his face, and there underneath was a second cover made of the same sort of net, I thought, as those covers like umbrellas which protected meat from flies in those pre-fridge days. He looked as if he were asleep, not quite real, and very still. He looked clean and his beard was neatly trimmed “his last-long sleep” my aunt intoned. And we all cried.

Next day was the funeral. All the blinds and curtains in the house had been drawn since the moment of death, and talk had been quiet and serious. The parlour curtains were now drawn back on their heavy brass rings and the sash window removed to allow the coffin to be lifted through because the doors opened onto each other awkwardly. As the undertaker’s men were seeing to this, the mourners, gathered in the garden, joined in the singing of John Newman’s hymn “Lead kindly light”, and they carried him shoulder high along the path, past his gooseberry bushes, and out to the waiting farm dray. This had been specially scrubbed and the carthorse, its brasses shining in the thin November sun stamped its feet, white fetlocks specially scrubbed for the occasion too. The hymn finished, the mourners were ushered into the funeral cars. In those days and in those parts, and in all families such as ours, there was a strict “pecking order” at funerals and blood relatives only sat in the first car: the widow and her two sons and two daughters. Then children-in-law came next with the grandchildren.

The mourners were mostly completely dressed in black from head to foot, but my mother, as a daughter-in-law, had under protest, managed to get away with a coat of large black and white dog-tooth checks, for she knew it would have to serve for several more winters to come. The men all wore hard hats, or bowlers. In those days if you didn't have one, you borrowed one for a funeral. Grandma’s hat had a full heavy veil, not unlike those worn by royal ladies at funerals, but Grandma always wore a veil to her hats and they were always gathered under her chin, as if she might have been going sit side-saddle on a horse.

The black edged “intimation” to the funeral announced that the cortège would leave the residence in Fryup Street at 12.30 for the service at Glaisdale Methodist Chapel at 2.30, and we started our long cold journey, fulfilling the words of the hymn we had just sung “o’er moor and crag …”. The mist and cold wind from the sea seemed to come right into the cars, for there was, of course, no heating. But eventually the horse was brought quietly to a standstill outside the chapelyard. I remember there were two more hymns inside the chapel: “Rock of ages” and “Abide with me”, sung this time to the accompaniment of a harmonium, which was played by a lady who also led the singing, which came in short spasms in time with her foot pedalling. Then the internment in the chapelyard with its drystone wall holding back the moor and its sheep. After the service, a somewhat quicker journey back to Fryup Street, but not very quickly on the moorland roads (funeral cars never did go more than a leisurely speed in those days, and motorists deferred to them). The band of helpers had taken the bed back to its accustomed room upstairs, they had flung open the curtains, though by now the November dusk was asking for them to be drawn again, and the black cloth had been replaced by a white one to accommodate the funeral repast.

___________________________________________________________________

My mother had recounted the story of the horse drawn coffin across the moors while we drove through Fryup Dale. She also told me a part of the story that my father didn't mention in his account - the fact that he and his mother got the giggles while the harmonium playing lady sang in spurts with her pedalling. I gather they rather disgraced themselves.

The following pictures show Thomas's wife, Betsy, outside Rowland House, together with a more recent picture of the house which was taken by my father probably about 20+ years ago.

|

| Chapel and chapelyard at Glaisdale where Thomas' funeral took place (photograph taken by my father at same time as the one of Rowland house) |

|

| Thomas Featherstone |

|

| Betsy Featherstone |

|

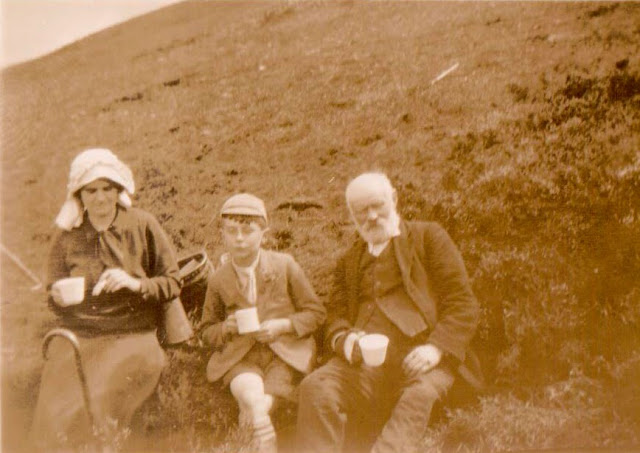

| My father, John Featherstone with his mother, Edith, and grandfather, Thomas, collecting kindling on Glaisdale |